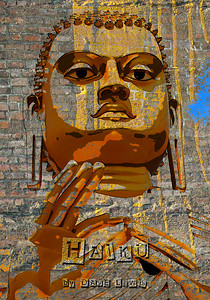

My sixth book is a modern haiku collection written over a period of a few years. Published in May 2012 by Ponty Press.

My sixth book is a modern haiku collection written over a period of a few years. Published in May 2012 by Ponty Press.

It should be noted that many of the ‘haiku’ in this collection would not be termed such by many, more academic observers. I certainly knew and appreciated this at the time but was, perhaps selfishly, more concerned with just simple self-expression. Especially as my wonderful little dog Sandy had just passed away. This collection not only helped me discover a new voice but was also extremely demanding to write. I decided that I loved ‘haiku’ because it gave me a means of recording the deepest of feelings in the simplest way. I knew that I would return to it again in a later book, and perhaps even attempt to create a more unacceptable version of the form.

‘Dave Lewis is a unique voice in the poetry world. His new collection is filled with a range of vivid, often quirky, word pictures. He is adept at making every word count. Despite its brevity, the haiku is anything but an easy option – at its best, this short and fairly formal poem should make the reader look anew at an everyday event. This Dave does to perfection, for example, “Chain gangs of electricity/on the green mountain/armies marching”. His haiku don’t always conform to the traditional 5,7,5 syllable format – he goes his own original way, as in a favourite of mine, “Consultant’s waiting room/the plant in the window/dead”… who else would have the temerity to finish on that single-beat word, dead? His thought-provoking images have some surprising last lines that take your breath away and will remain with the reader for a long time.’ – Moira Andrew

This book can be purchased direct from the publisher as a paperback for £6.99 (plus postage) or as an e-book on Amazon kindle for £3.99.

Introduction

Haiku is a small poetical form, usually but not always of three short lines, that attempts to juxtapose two images or ideas. The separation of the elements creates a sensation or emotion in the reader. A haiku captures a ‘moment’ in time, perhaps a mood, or a sound, a smell or a taste and forms a complete living entity. A good haiku, like any good poem, is distilled and paints a vivid picture which the reader must complete.

Haiku originated in 17th Century Japan and seems to have evolved from the earlier 14th Century ‘Renga’ (literally: linked songs) – a collaborative form with strict guidelines and great length. Haiku as we know it today derives from the opening verse of renga.

Many early Japanese poets were monks or teachers and one of the most famous of these was Basho (1644-1694), who was a Zen Buddhist. This is important when we look at the make-up of a traditional haiku. We get the moment of instant perception and simplicity from Buddhism whilst the Zen brings us a de-emphasizing of knowledge in favour of direct self-realization. Thus haiku can be viewed as a ‘mind set’ or ‘spiritual way’.

After losing its way slightly haiku was made accessible to wider audiences again by the great poet Issa (1763-1827), whose unhappy childhood and hugely tragic life is present in much of his poetry.

Other writers, like Shiki (1867-1902), modernized haiku as they disliked much of the current trends in Japanese literature and were heavily influenced by Western culture. He created a style of haiku known as ‘sketching from life’ and it was Shiki who is credited with separating the first stanza of a renga and allowing it to stand alone as a haiku.

The mid-20th Century saw writers like Blyth and Henderson seeking to translate Japanese haiku and make it more accessible to the West while imagists like Ezra Pound (1885-1972) stressed the importance of brevity, directness and music in all poetry.

Pound felt that an image should avoid parable and even metaphor, and be capable of being grasped instantly. His famous ‘metro station’ piece became a precursor for modern day urban haiku, where topics such as cars, buildings, computers and shopping centres are all fashionable subject matter nowadays.

In the 1950s the beat generation of poets became endeared and liberated by haiku. Jack Kerouac (1922-1969) often put haiku in letters and in the middle of novels as a means of pinpointing a particular moment in time and place.

Alan Ginsberg published haiku throughout his long career, and in 2004, at the age of 74, Gary Snyder was awarded The Masaoka Shiki International Haiku Grand Prize for his contribution to the art of haiku internationally.

Today there seems to be almost two schools of thought:

The stricter and more traditional approach, in English, is to use three or less lines with 17 syllables, add in a seasonal word (or kigo) and a cut (sometimes indicated by a punctuation mark) to highlight where the reader needs to contrast and compare two images.

To use the present tense of the verb in order to preserve ‘the moment’ is encouraged as well as obeying several other rules like avoiding simile, metaphor or personification.

However, in modern society where many of us are pushed further away from the natural world, haiku, like all poetry, has evolved to become ever more urban based and so I believe it is therefore important to have a broader approach to haiku and to reflect these new sources of inspiration. And today it is almost impossible to categorise any particular style, format, or subject matter as definitive.

Therefore in the more radical haiku a modern proponent may abandon the rules completely and instead of focusing on nature may illicit hi-tech gadgets, inner-city living, iPhones and technology in their writing as well as using a change of form, line break, punctuation, shape and length.

Kerouac himself wrote ‘…a haiku must be very simple and free of all poetic trickery…’.

But, there are single line haiku (monoku), two lines, four lines, ‘vertical’ and ‘circular’. In fact almost anything goes as we see haiku evolution changing its focus and influence in our ever-changing 21st Century world.

As a result almost anyone can write and understand a haiku. And as a hard copy record of the precise instant of inspiration and experience there is no better form.

From my own personal viewpoint, whether in art, photography, poetry or music I believe all rules are meant to be broken and so with regards to haiku whilst I often revel in the moment and have a dislike for ‘over-creating’ for the sake of it I do concede there is room for a small degree of ‘crafting the moment’, maybe just tweaking that emotional outpouring to render it more lucid or universal.

For as the great haiku advocate Jane Reichhold says ‘Perhaps, nothing is absolute in haiku. Like life, haiku require learning, experience and balance.’

Many haiku writers use the five elements of Taoism as the themes with which to organise their poems. The antagonistic yin and yang approach of using wood, fire, earth, metal and water links in well with the natural aspect of haiku where the energy of the cycle is either productive or destructive.

When thinking of some sort of structure for this particular collection though, I decided to use the four seasons as headings. I was amazed, but not surprised, to discover my writing adjusted with the changing time of year and also as I found myself becoming drawn more and more into the genre.

As for the quality of the haiku I will of course let the reader decide but rather than omit a few lesser poems I decided I could afford to be a little extravagant in order to fully record my own sense of time and place in this ever-changing environment we all find ourselves struggling to cope with. That said I’m sure I will continue to write haiku and in the years to come will hopefully have many more to share.

And finally, although not 100% convinced it was a good idea, having seen it in many haiku collections, I eventually decided to include at the end of this book some brief notes which may help to explain certain moments a little better.

Either way I hope you enjoy reading these poems as much as I enjoyed living them.

Dave Lewis

Spring 2012

Sample poems:

St. David’s Day –

Eve has two daffodils

one for her doll

June rain –

you smile

before leaving

butterflies

in the spreading oak tree

– heart murmurs

bowing elephant

at the sacred relic of the tooth

hot sun

Thrush on the ground

next to the sycamore branch

Still bobbing

Sweet Spring rain

on my lips –

the cracks in a wall

black ice –

another makeshift shrine

at the roadside

Reviews:

‘Unconventional, unapologetic, unpretentious! Dave Lewis’ Haiku gives us an interesting taste of outside-the-box thinking and reminds us that while we breathe, we can embrace change, bend the rules and though we walk the same path as many others before us, we can make our own tracks.’ – Jolen Whitworth

‘Haiku linked by place, people and the seasons: full of subtle moments.’ – Mike Jenkins

‘A vivid and memorable first collection of haiku by a talented poet. Dave Lewis takes us from Pen y Fan to the Transvaal; from nature’s seasons observed in close-up to intensely personal and poignant revelations. A must-have for fellow-poets and the general reader alike.’ – Sally Spedding

‘Dave’s book is free from pretentions, there is good variety, and good quality throughout; he’s clearly put a lot of thought and attention into this work.’ – Nick Fisk

‘Modern Haiku which addresses the everyday and yet somehow brings out those snapshot insights that resonate with the reader. This book comes highly recommended.’ – Mark Treacher

You may also like: